Why Beta Readers are the Secret Backbone of Writers

Wikipedia defines a beta reader as the following: “a non-professional reader who reads a written work, generally fiction, with the intent of looking over the material to find and improve elements such as grammar and spelling, as well as suggestions to improve the story, its characters, or its setting. Beta reading is typically done before the story is released for public consumption. Beta readers are not explicitly proofreaders or editors, but can serve in that context.”

This, though, is the most important part of the definition: “Elements highlighted by beta readers encompass things such as plot holes, problems with continuity, characterization or believability; in fiction and non-fiction, the beta might also assist the author with fact-checking.”

So a beta reader can, and may, do everything. It’s important for potential beta readers to discuss what they want out of the exchange in advance — hey, give me a total read-through, any feedback at all, or maybe just tell me what you think of my protagonists’ emotional arc.

While the specific functions can vary between beta reading gigs, I think the most important function of a beta reader, the non-negotiable role and PACT, is that of assessing plot holes, problems with continuity, and characterization. If you have a beta reader that hasn’t looked out for these things, then you don’t have a beta reader at all. They’re just a reader.

But why beta readers? I didn’t realize until recently, as I began an intense foray into the world of soliciting and acquiring new beta readers, that some writers don’t use beta.

I’ll give you a moment to recuperate, as I sure needed to gather myself after learning this.

What would compel someone to avoid beta reading? I looked into this, since the logic just didn’t compute. Outside eyes + lack of bias = suggestions or commentary that the author could never see on their own. Beta means better, as far as I’m concerned.

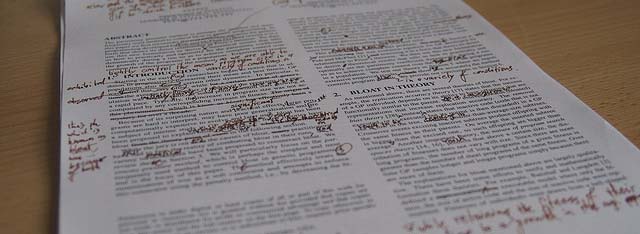

That’s not to say every beta reader will “get” your work the way you want them to. Maybe they won’t even like it. Maybe they’ll love it. But all of that feedback, commentary, questions, praise, criticism and concerns that we get back from a beta reader are inherently valuable, whether or not they are all used in the final version. As Michael Kinn writes in an article (link at the bottom) about beta reading etiquette, “But even if they shred our work, drench it in motor oil and bounce the papier-mâchéd blob off our skulls, we thank them sincerely for their hard work.”

In communicating with fellow authors, I began to see that some were avoiding beta because their experience with it was not equal to better. Beta, in their experience, meant bummer. Why? Not because of the papier-mached blob bouncing off their skull — something that is actually useful from time to time. Beta=Bummer because there was no constructive feedback coming in. It was pure “Oh, I love this novel so much”, or “This is great, wouldn’t change a thing” or, the worst of them all, sugarcoating.

I’ll go ahead and say it: sugarcoating has no place in beta reading.

This doesn’t mean you have a free pass to be a total asshole. But rather, tip-toeing around fragile egos does not help either party involved. As a beta reader, we are not tasked with placating or pandering to the psyches of the author. Our job is not to avoid saying what we really think about a piece because they might disagree or get offended. What we are tasked with is delivering insightful commentary in a helpful manner.

The goal is to build up — not tear down. Sometimes commentary can feel like it’s tearing down — don’t we all harbor that secret wish that we nail it on the head the minute it leaves our fingertips? The goal is to improve a piece, to offer honest-to-god thoughts about this plot line and the characters involved, because any seasoned writer knows that the secretly harbored fantasy of perfect first drafts is laughable, at best.

For me, beta reader is one of the last steps — I’ve written the whole thing, revised it once or more on my own, and then it’s time for beta. But it is a CRUCIAL step before submitting anything to an editor or agent. If my piece does not get beta read, I feel it is incomplete, hands down, no bones about it. It is a naked work of art, half-finished, trembling in a corn field waiting for the combine to come through.

(WTH with that analogy? I suppose the combine is the revision process. Anyway. Maybe i need a beta reader for this post. Moving on.)

For me, the more eyes the better. Just as much as I like to know that a reader loved my piece, I can’t reach a higher level as a writer without knowing where my weak spots are.

Beta reading is the truest service we can offer one another. It is a gift that authors can and should exchange. It costs nothing but it is worth more than anyone can accurately describe. I feel emboldened by and proud of the exchanges that I maintain through beta reading.

Plus there’s the added benefit that when I beta read someone else’s work, I come back to my own pieces with fresher eyes and a sharper knife…er, delete button.

It’s easy to understand, though, why some writers would avoid beta readers when sugarcoating and unhelpful praise constitutes the bulk of their feedback. We owe it to ourselves and to our fellow authors to be honest and helpful. Take a firm stance in the spirit of mutual betterment.

Don’t be afraid to tell us what you think. Nobody gets better by avoiding or sugarcoating the truth. Be honest yet tactful — and relish in your good deed done for all authorkind.

Offered in service,

Ember

OTHER ARTICLES ABOUT BETA READING:

Jane Hardy’s Fiction University looks at beta reader etiquette here: On Critique and Beta Reader Etiquette, by Michael Kinn

Women on Writing look into beta readers in this article: Shedding Light on the Role of a Beta Reader